What Are Coxeter Dynkin Diagrams?

Dependencies: I will assume you know what the basics of polytopes, know about uniform solids, and know Schlafli symbols. If you aren't already comfortable with those topics, this may be a bit hard to follow.

If you're anything like me 4 months ago, you LOVE polytopes and have seen Coxeter Dynkin diagrams a lot, but find them extremely confusing and can't find any info on them. Fret not, I will attempt to explain! They actually are pretty simple, it's just that no one has bothered to make a good explanation of them yet.

The way I'm gonna explain this is I'm not gonna go through how they work, I'm just gonna go through how to use them. You don't need to know about the inner workings if you just want to read and write them. This page will start off weird and abstract, but if you stick with it long enough, it'll make sense.

Also, the stuff on this page is sorted by most important to least important, so don't be intimidated by the length of the page. After the first two chapters you're basically good to go, but if you want to learn more, you can.

Symmetry Groups

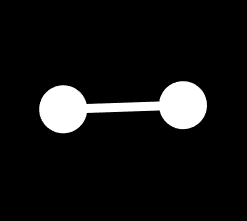

Let's start with Coxeter diagrams. They're like Coxeter Dynkin diagrams, but all nodes are unringed. Below is the diagram o3o, as it has no ringed nodes (written with an x instead of an o), it is not a polytope, but rather a symmetry group. The edge connecting the two nodes doesn't have a label, but as you might've guessed by the written transcription, the unlabelled edge means 3. But what does 3 mean?

"3" means the 3 sided regular polygon, so this diagram represents the symmetry group of the triangle, A2*! If you feel lost and confused because you don't know what these nodes are or why we're connecting them, just hold on for a bit, it'll make more sense when we get to Coxeter Dynkin diagrams.

*There are two systems for writing symmetry groups. The one with Oh and Ih is not the one that is used when discussing polytopes, as it does not generalize well. When I say A2, that is not the order 1 alternating group of 2 elements, but rather the order 6 symmetry group of the 2-simplex.

As you might expect, the Coxeter diagram below is the symmetry group of the regular octagon, also called I2(8). Written o8o.

.png)

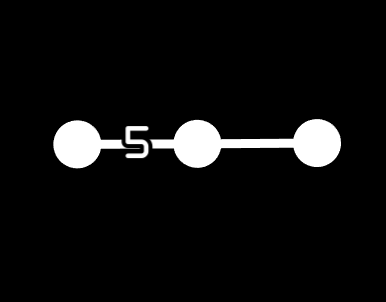

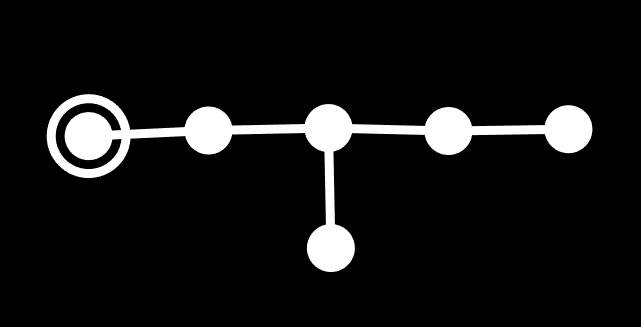

Alright, enough rank 2 symmetry groups, what does a rank 3 symmetry group look like? Well, it has 3 nodes, since a Coxeter diagram with n nodes has rank n, and if it's linear it has 2 edges. What is this symmetry group? For linear diagrams like this, it's equivalent to a Schlafli symbol, so this is the symmetry group of {5, 3}, or H3. This would be written o5o3o.

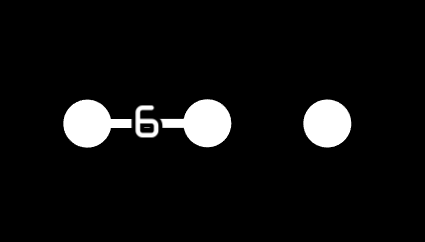

Lastly I want to cover this diagram. What is this? It's not connected, is that even allowed? Yes actually, any two nodes that aren't connected actually are, and they're connected with a 2. That means this diagram is the symmetry group of {6, 2}, which is degenerate, but if you think about it a bit you might realize this is just a silly way of saying hexagonal prism symmetry. This symmetry group is written G2xA1, or I2(6)xA1. This diagram would be written o6o o.

Worth mentioning that disconnected Coxeter diagrams are the cartesian product of their components.

That's about everything for symmetry groups. Non linear diagrams are a lot more complicated, but they're really hard to intuit in your head even if you know how Coxeter Dynkin diagrams work under the hood, which I don't plan to teach you since it's not that useful and just makes them appear scarier. Non linear diagrams are pretty easy if you're thinking about them as polytopes, but as symmetry groups there's not much you can do besides memorizing the names. Only linear diagrams have simple intuition about Schlafli symbols and stuff.

Before you go to the next section, I recommend looking at this chart if you're not familiar with these symmetry group names already.

Uniform Polytopes

Now that you understand the symmetry groups generated by Coxeter diagrams, how do you get uniform polytopes from them?

You can ring nodes to activate a part of a diagram. In the written diagrams, these are notated with an x. Then by removing and re-adding different nodes of a Coxeter Dynkin diagram sequentially, you can find its facets. If there are no regions of the Coxeter Dynkin diagram that lack ringed nodes, then it's a facet, otherwise it's just a lower rank element with more symmetry.

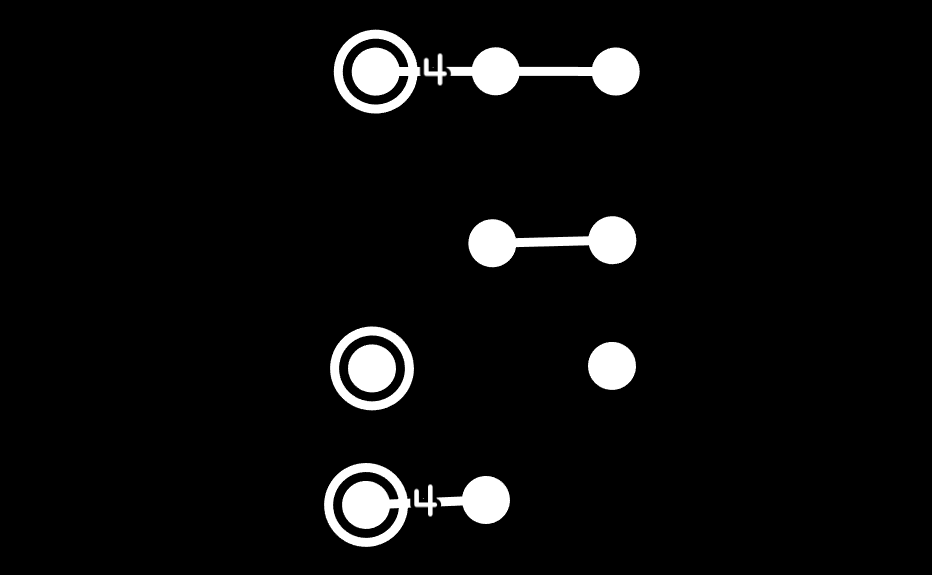

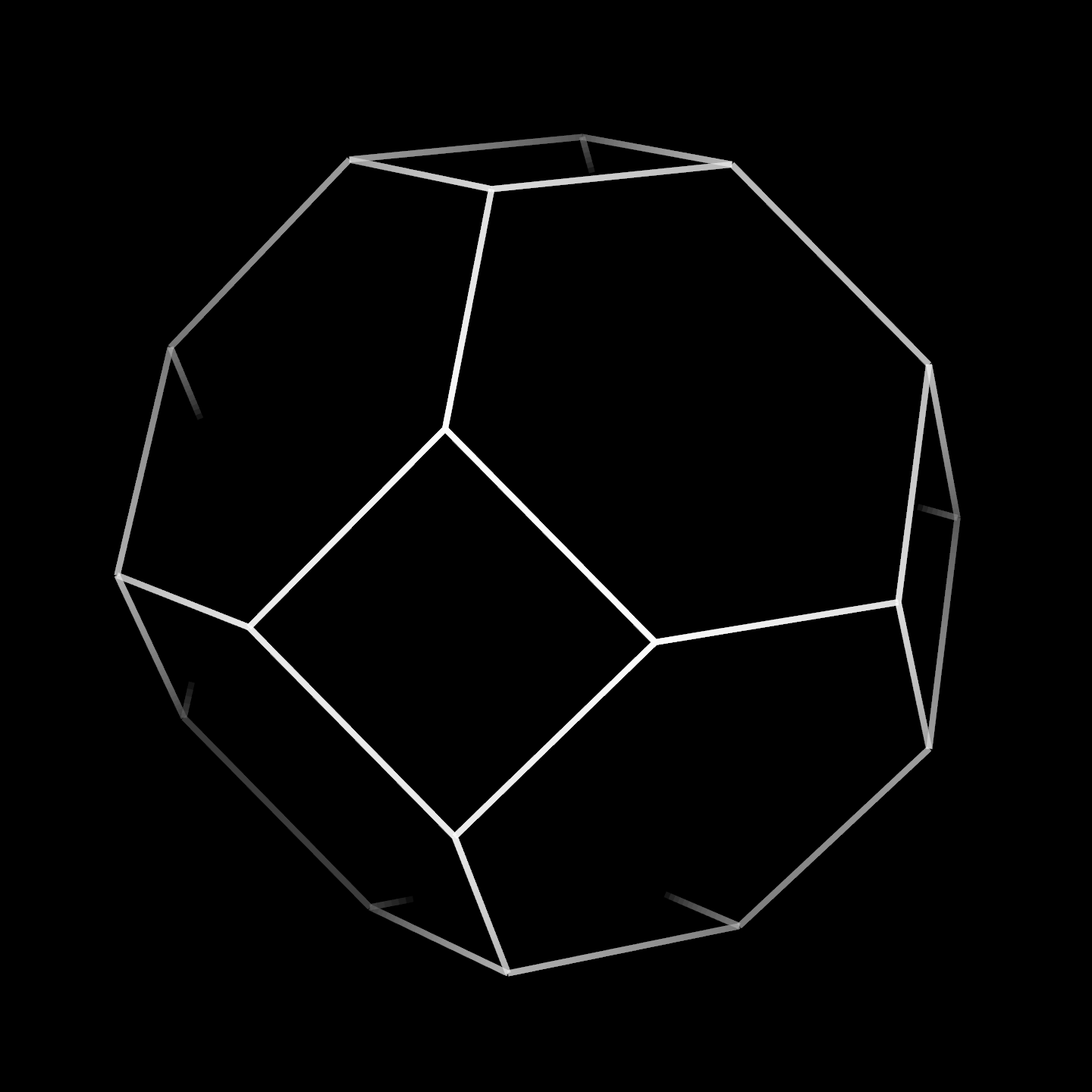

Below is a Coxeter Dynkin diagram with B3 symmetry. If you cover the first node, you get unringed A2, which is invalid. If you cover the second, you get A1xA1 with one section unringed, making it invalid. If you cover the last one, you get B2 (square symmetry) but with one ringed node. That means it's valid! When polygonal Coxeter Dynkin diagrams have one ringed node, it just means they're a regular polygon.

Since this thing has cubic symmetry, and it only has square faces, you can probably guess that it's a cube.

But what about this? It has A3 (tetrahedral) symmetry, but it has strange x3x facets. What are those?

Well, think of it this way: o3o is triangle symmetry, right? What do those two nodes represent? Well, one of them represents the 3 vectors pointing towards the edges, and the other represents the 3 vectors pointing towards the vertices of a triangle. When both are unringed, you just have symmetry, with no polytope. By ringing one node, you're pushing vertices out in that direction, and then the edges go along with it. If you then ring the other one, those 3 edges move outward in the direction of their normals, and you get 3 new edges.

Something worth noting here is that that means x3o and o3x are slightly different. On their own, they're identical, but in the larger context of a polytope, they are actually rotated 60 degrees from each other, and that matters. For example, the triangles of an octahedron (x3o4o) are rotated 60 degrees from the triangles of a cuboctahedron (o3x4o).

This makes a semi-uniform hexagon, or more commonly, a perfectly regular hexagon that has A2 symmetry in the context of the polytope. So for the diagram above, that's the truncated tetrahedron, and its hexagonal facets are connected to 3 other hexagons and 3 triangles, in an alternating pattern, meaning it only has triangular symmetry.

Expanding On That Expansion Idea

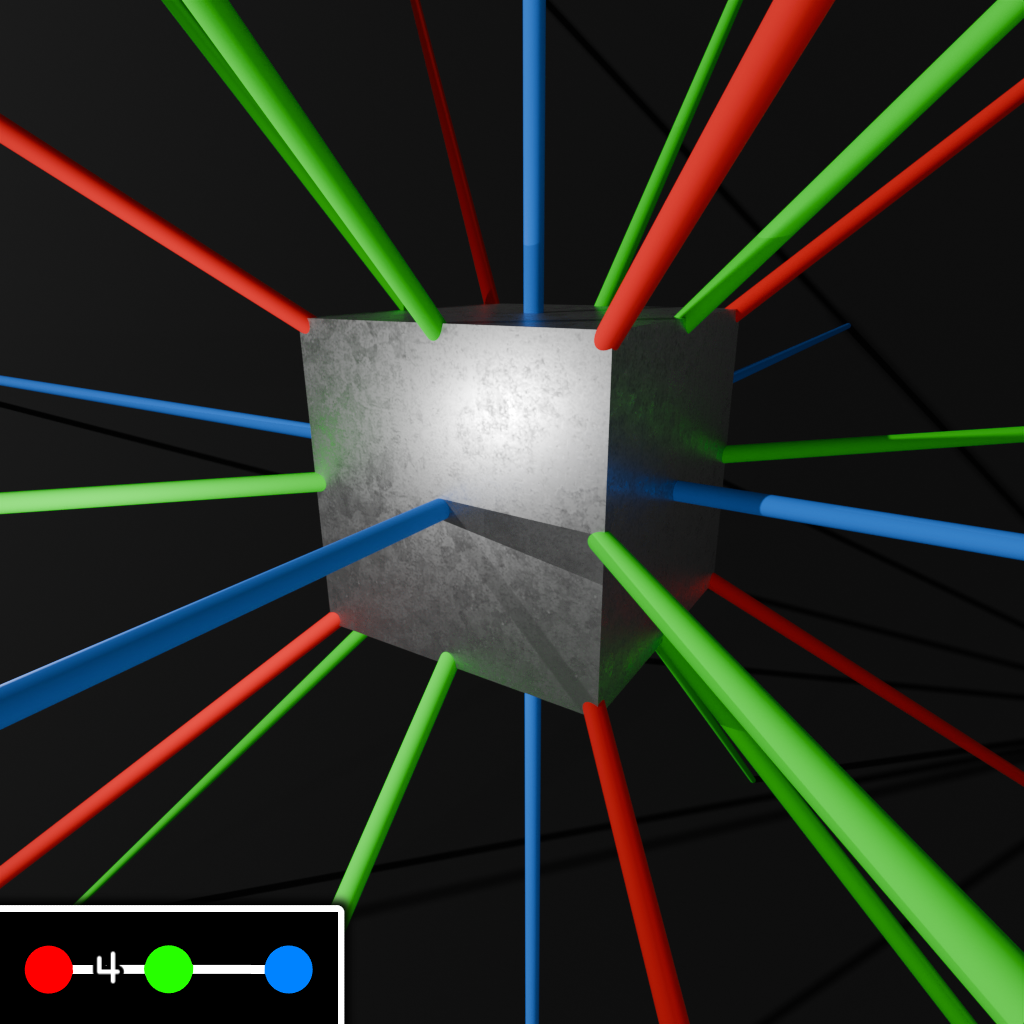

Nodes corresponding to sets of vectors is a really useful way to think about Coxeter Dynkin diagrams. In the image below, you can see why ringing the red node of B3 gives a cube, and why ringing the blue node gives an octahedron.

Now say we have a truncated octahedron, or o4x3x, like in the image below. If we ring that first node, the hexagons will be pushed out by the cube vectors, and the squares' edges will be pushed out as well. Try to imagine what that shape would look like. If you think you have a good idea of what it looks like, check if you were right.

I hope by this point you understand getting facets pretty well. You just cover nodes sequentially, discarding facets that have unringed regions. But something interesting that I mentioned earlier was that the unringed regions are lower rank elements.

For example, if we have an icosahedron, x3o5o, by covering that first node we get o5o. This is telling us that its vertices have pentagonal symmetry. If we cover the second node, we get x o, which is A1xA1, or rectangular symmetry. This is because the edges have reflection symmetry. Pretty neat!

I encourage you to now try going from 3D/4D Archimedean solids to CD diagrams and vice versa on your own to see if you get it. You can use the polytope wiki to search the written CD diagrams, to see if you guessed it correctly.

Vertex Figures

How do you get vertex figures from these? For quasiregular shapes, aka shapes with only one ringed node, it's pretty simple. Remove that node and ring its neighbors. So for a cuboctahedron, o4x3o, it's x x, a rectangle!

For anything else it's insanely complicated and I have no idea how to do it.

Non Linear Diagrams

If you're like me from 4 months ago, you've probably heard about E symmetry, but couldn't figure out what it was and found it really baffling. That's because you need to understand Coxeter Dynkin diagrams to understand it. Now that you understand those, I will explain!

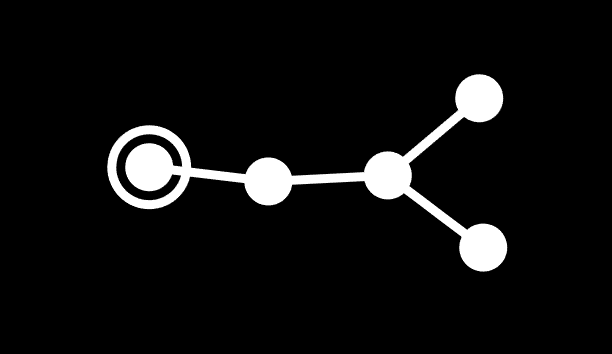

The diagram above is the hexelte, which is the simplest uniform E6 polytope. It's also more commonly called the 2_21 polytope, because the one ringed node has 2 nodes until hitting a branch, and then the two branches after that are length 2 and 1. So something like a rectified pentachoron would be 0_21.

If you take a second to figure out its facets, you'll see it has two types. The first type is pretty obvious, it's just a 5-simplex, but the other one is weird.

What is this mysterious object? Well, it's the 8 op 5-demi by my naming scheme, also called the 2_11 polytope. It has D5 symmetry (half penteract symmetry), and it has two types of pentachoral (4-simplex) facets. Its vertex figure is x3o3o *b3o (we use asterisks followed by a letter a-z to denote where it branches off from), which is a 4-demicube, also known as the 4-orthoplex. Wait, it has all pentachora, and it has a 4-orthoplex vertex figure... this is a 5-orthoplex!

This is something really interesting about uniform polytopes that I didn't really appreciate before learning CD diagrams. Which is that polytopes can be identical whilst still being different. For example, there are a few 5D Archimedeans with 24-cell facets, but they're not really 24-cells, since there is no spherical F5 group (more accurately there are no non prismatic spherical 5D symmetry groups that have F4 as a subgroup). What are they then? They're rectified 16-cells!

So yeah this hexelte polytope has 5-orthoplices and 5-simplices as facets. The 5-orthoplices connect to 16 other 5-orthoplices in an alternating pattern, and the remaining 16 facets are connected to 5-simplices. This is why the 5-orthoplices only have D5 symmetry, rather than B5.